It was difficult to find this place. Everything has changed.

I consult an old map, where the old names of the prefectures before the Meiji period are shown, the time when Japan opened up to the West. Most of what used to be Shimosa once is now Chiba prefecture.

The first time I came across the name Chiba was in William Gibson’s iconic cyberpunk novel Neuromancer. Set in a world in the not so far future, humans enhance their bodies with implants, nerve splicings and microbionics. Chiba is the marketplace for all these gears, while Tokyo Bay serves as the liquid background to this liminal space.

Years ago, I stayed in Chiba with my friend Susumu and his family. It was a high rise complex from the mid-seventies. Father, mother, grandmother and Susumu lived in a tiny apartment. The first thing he showed me was the spot on the apartment building where people jumped from. Everything in this town felt estranged, empty and void. In the evening we went to a gigantic hot bath house and ate clams and shells that were so fresh they still moved on the ice of the plate.

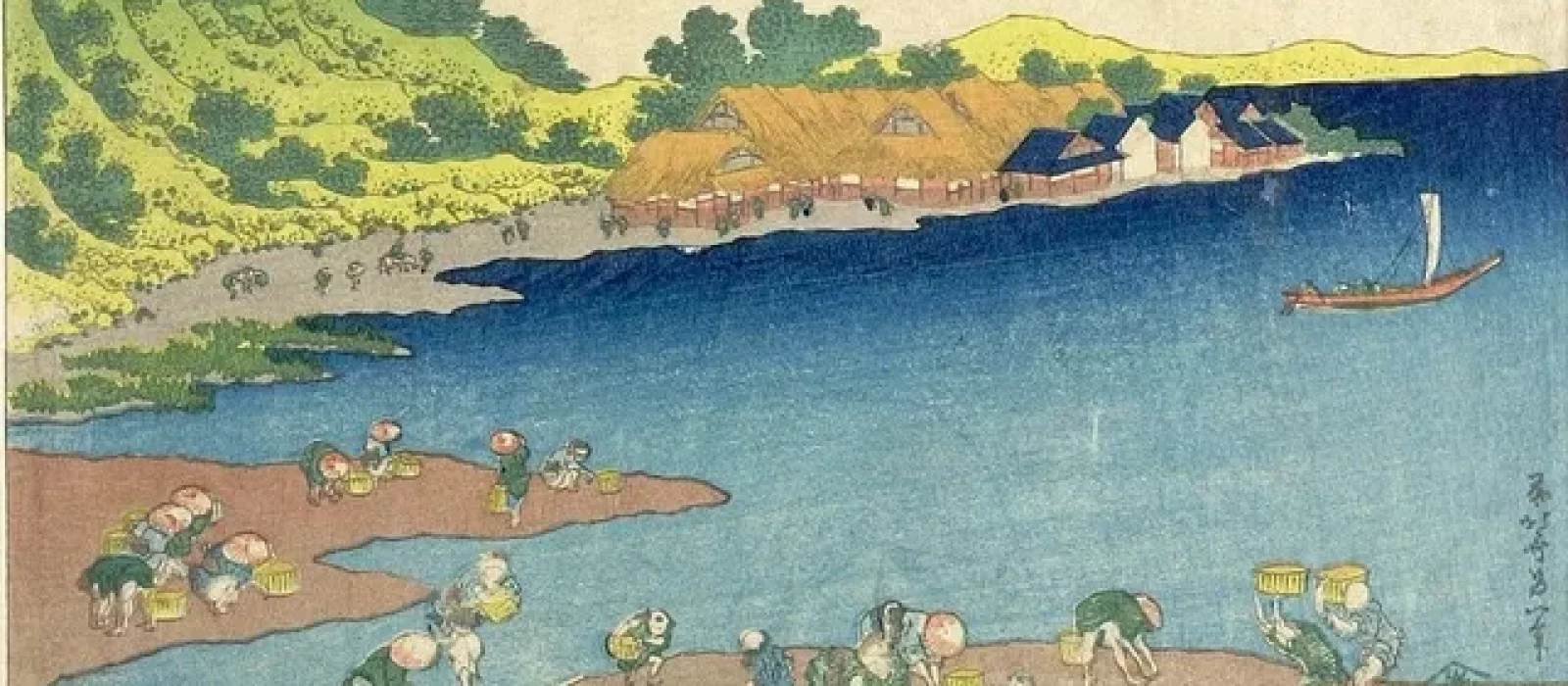

Hokusai’s woodblock print shows an idyllic shore, with a slightly hilly coastal line. The tide is low and the sand beach extends far into the sea. The water is vital and blue, thanks to the newly introduced Prussian blue pigment and the skill of the printing workshop that turned Hokusai’s sketches into enduring jewels.

In the print, the sea in the bay is calm. Various men are engaged in shiohigari, or clam digging. Asari, Bakagai, razor shell, clams would have been their harvest. The tidal zones are some of the richest productive areas in the world. One needs to dig only a little bit to find an abundance of food.

Noboto does not exist anymore. It is now Nobuto, as it lost its name in the 60s, when the Chiba shoreline was filled in and Noboto’s beach was turned into Japan’s biggest port. There still is a beach 4 km north of this oceanfront at Inage seaside park, the longest sand beach in Japan. Imported from Australia, the sand is said to give a sense of Honolulu. On my visit, strong winds churn the waves and the clouds move strong over the bay. In the distance, the factory towers of Tokyo form a grey industrial skyline.

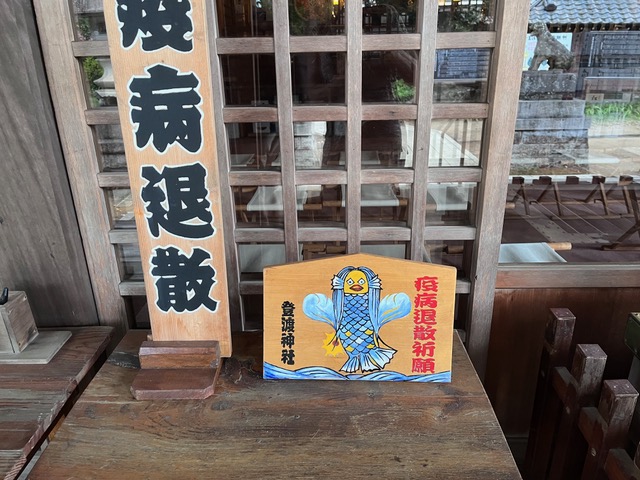

The name Nobuto only appears at a shrine and a train station on the Keio line with the name Nishi-Nobuto, or Western Nobuto. The shrine is not far. I walk along a double-lane street, past a wedding hotel serving autumn cakes filled with chestnut cream. After a kilometer inland the terrain rises, and I climb the stairs to the shrine. The city disappears. Cicadas sing and crows watch my steps from old trees. I am confused, as the name Towatari shrine also appears on Google maps. In reality, Towatari shrine, which was built into the water in the Noboto Bay, was moved not long ago and now seems to be housed here with the Nobuto shrine. Here are two shrines of places that do not exist any more. I see a light burning in the office of the shrine priest and knock on the sliding door. The old man opens them for me and looks me up and down. “Why are there two shrines here now?” I ask. “How do people now express their gratitude for catching fish and collecting clams, to live on?” “Things have changed.” The priest says. “The fish catching now takes place far out in the sea. There is no shore here anymore. People work in companies. They work for trade and other businesses.” “So what do they come to the shrine for then?” “They now are grateful to other things. The usual, you know.”

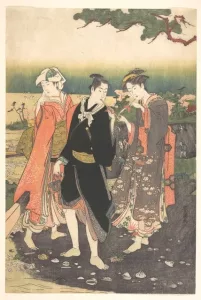

There is another print by the Ukiyoe artist Utagawa Toyokuni titled “On Shinagawa beach at ebb tide,” from roughly the same period. Men and women in elaborate kimonos visit the beach to enjoy the tidal flatlands. There is s slight sexual tension in some of those prints, suggesting that clam digging might have been a fun dating pastime for Edo city people.

Shiohigari, clam digging, is now a popular leisure activity during the late spring and summer months for families and groups of friends around Tokyo. Being outside for a day, a treasure hunt of sorts.

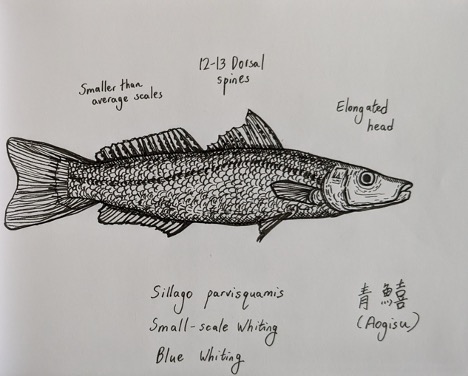

A small-scale whiting (Sillago parvisquamis). Once a common species in the tidal flats around the village of Urayasu, it is now believed to be extinct in Tokyo Bay due to urbanization and land reclamation efforts. Encountered at the Urayasu Folk Museum in Chiba Prefecture.

Sketch by Isaac Yuen