Aiko and I arrive at the same time at the parking lot of the Sea-Folk-Museum of Toba. She drives a sand coloured Suzuki Jeep, and I immediately recognise her I have been following her on instagram for over a year, drawn to her underwater photographs of kelp forests and her accompanying words on the seasons under the sea. Aiko is a modern Ama diver, Ama meaning “woman of the Sea.” The UNESCO World Heritage website states that the Ama arrived to Japan as an anarchistic group of womensome 3000 years ago. In a society that systemically puts women behind men, the Ama have been looking after themselves, raising kids, supporting their families with the one skill they have: to dive and to collect shells and other seafood. Ama can still be found along the coast of Japan and Korea, but their numbers are dwindling. Their daughters wouldrather move to the cities than stay in the remote countryside. Aiko, however, is drawn to the sea. Even though she was raised in Tokyo, she now is a practicing Ama in Toba, Mie Prefecture.

We sit in the little museum cafe overcoffee. Her hair is still wet from her last dive and she needs something to pick her up. In this season she goes diving twice a day for exactly 1 hour and 10 minutes each dive. On a good day, she will come up with 10 kg of abalone shells. What made her become an Ama?. She starts from the beginning. How she has always loved the sea. Growing up in Tokyo, she studied art and became a photographer. One day, she saw an ad that they were looking for young women to learn Ama diving in Toba, a seven hour drive south on the Kii peninsula. She decided to give it a try. How does one learn to be an Ama? Aiko laughs. “By doing it!” She recalls how the older Ama divers just took her with them and said: Dive. And she did, not knowing what to do. Over the course of the next three years, she would learn how to spot abalones on the sea floor, how to pick them up and how to manage her body. She tells me how many calories she burns each season and that the only way to keep her strength up is by preparing her own recipe of Ama-sake, a sweet fermented rice drink that has not turned alcoholic yet. It is a high calorie, high nourishment kind of brew that warms a body that spends a lot of time in the cold Pacific ocean.

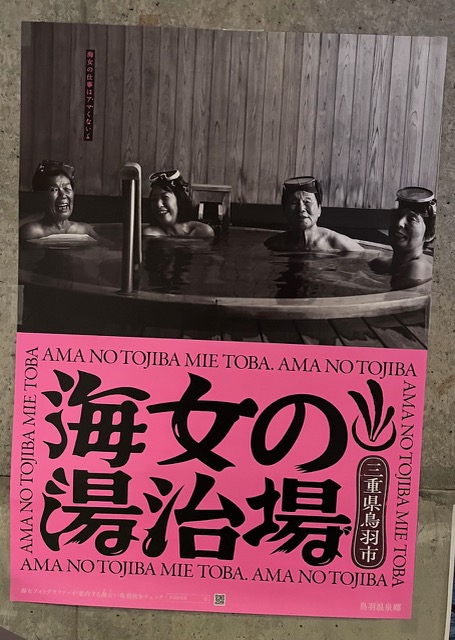

The abalones are not easy to find. Later, in the museum exhibition, I play with an interactive display where I put on diving goggles and see through the lens of an Ama. I glide over the sea bed, looking out for abalones. It is summer and the sea is murky; I can only see as far as my hands. The winter months provide better vision, but also colder waters. The abalones look exactly like the rocks they sit on. Without a trained eye, they seem indistinguishable from their surroundings. The next thing to learn is how to navigate under water. An Ama spends approximately 50 seconds before coming up for air, hopefully with an armfull of abalones. She puts them into a floating basket and dives again. What Aiko had to learn and get used to internalising the underwater landscape. She has around one square kilometre of territory that she is responsible for, by now she knows the terrain. It took a while to become familiar with it. “I come up and find the mountain on the shore. Then I connect it with the rocks under water.” But mostly she learned through the stories in the Ama Goyas, huts on the beach where all the Ama would meet afterwards and share their knowledge. Here they take off their wetsuits and dry their bodies near a fire. Laughter fills the Goyas, and one never sees a photo of the interior where an Ama is not laughing. “Why is this so?” I ask. Aiko shows me the talisman the Ama use. One is a star drawn in one line calledthe domen. One enters the water at one point, goes around, and comes up again. There is no space for evil to enter. The other talisman the Ama draw on their clothes and tools is called the seimen, a kind of grid, window-like. Many eyes watch out for one another. Evil does not know where to enter.

Being in Ama is dangerous. The sea is unpredictable. This year Aiko lost a dear friend, another Ama diver who was 85 years old. No one knows what exactly happened, but she might have swallowed too much water and drowned. She had been diving 70 years.

“When the sea is too rough, we don’t go out. This is one of the points where we are different to the male divers.” I have never heard about male “Ama” divers before. It’s a new trend, Aiko explains. Because there aren’t enough women to follow in the tradition, men are allowed lately to join as well. “But they do things differently and that is not always good.” she says. Male divers push harder. They will take out more abalones and go in any kind of weather. Aiko feels they take too much and don’t leave enough for the next year.

A female Ama will listen to the sea and her body and try to sync. Aiko does yoga to feel more into this connection. “It´ss hard enough, to be underwater for so long, but if you are not feeling into it, it is meaningless.” There are many myths about Ama and the abalones. The shells are said to give themselves to the Amarather than the Ama taking them. On days when an Ama has a memorial for a deceased loved one, the abalones seem to offer themselves in abundance. “I dontt know why that is the case, but it really is like that. On such a day when I dive, there will be crevices full of abalones and none of them will run away. I come up with so much.” On days like that, she sends fresh abalones to her parents and friends in Tokyo.

An Ama never takes too much. An Ama also stewards the seafloor. In these days of climate change, a lot is happening under the surface of the water.. The Ama who dive regularly make notes of the changes and report back: Less seagrass, too many urchins, the state of the kelp forests. Then they act accordingly. Pick more of this, leave more of that. It is almost like taking care of a garden, but more than that.“I worry what will happen when there are no Ama around anymore. Who will keep an eye out for these beautiful ecosystems?” Just a couple of bays north, the Ama lost their jobs because the seagrass died and no life is to be found.

Aiko loves her life, the balance of it. Swimming every day. In the hours she does not dive, she works for the city office PR department. Just now she is preparing to go to Paris, where the mayor of her town will meet with French mayors; they want to promote tourism in Aiko´s new home. Most excitingly, her photos are being exhibited. So far all the Ama photos stem from male photographers, perceiving slithe bodies slipping beneath the waves. When James Bond solved a case in Japan, he of course is entangled with an Ama diver.

Is it always so easy and carefree with the Ama? “They earn enough money to make a living, but no-one pays their retirement money or health insurance. Often they paid for the houses of their children and are proud of doing so. But not all of them chose to become an Ama Some tell of how they were not allowed to finish school and had no other job to go dive. But eventually, they all grew into it.”

The music at the cafe is easy, an island kind of music, care-free. I look forward to meeting Aiko again. There was something about her feeling me out during our exchange. And I liked that, the Ama way, the gift of connection, the sharing of stories.