I call Rimi Tanaka, a local fisherwoman, and arrange to meet her at her office in the harbour of Nigishima, Kumano, on the Kii peninsula. She is fine with whatever: “I will be there,” she says. The village is on one of the three routes of the Kumano Kodo, the pilgrimage path to Kumano. It is remote. Small islands outside the bay shelter it from the sea beyond, the mountains in the back cut it off from the mainland, and a small river feeds into its harbour.

After leaving the highway, we follow a narrow road hugging the coast. Only one car can pass at a time. Ever so often I need to stop because traffic comes from the opposite side. Not for the first time, I am thankful I chose the smallest car, a Nissan Bolero, at the car rental in Tokyo, now so many days and so many encounters away.

One bay after another, the road curves, shaded by the hinoki, or Japanese cypresses, that cover the hills. They are a dark, satisfying green that draws in the mists and sends them upwards as feathery clouds. Ever so often, an opening in the forest reveals a view on this coastal interplay, and I allow myself to stop at one curb and get out to take in a deep breath. The hush of ocean waves from below, the slight rain falling from above, forming the kind of background noise that calms and nourishes. But then the cars come and I need to get back on the road.

There is a grey layer over Nigishima. Where the mountain road meets the harbour stands a small pavilion. A lady sits inside, smoking a cigarette. On a bridge, someone catches fish under an umbrella. A heron sits and waits. I park the car next to some vending machines and walk the last few steps to the address Rimi gave me.

The house is three stories high, a concrete building from the 70s, aged and used. Crates and nets are piled in front, along with some steaming machines and pink coloured fishing rubber trousers. I call and Rimi-chan comes to the door. “Hey, you found it.” She is all smiles. She urges me to sit down inside. The room is crammed with stuff, but a small table is clear with two chairs. She puts a plastic bowl in front of me. “Here, eat first. My mum made this.” It is a bowl of fresh maguro-don, chunky sashimi tuna slices on rice with seaweed sprinkled on top. “Use the wasabi as well.” She watches me eat, and when she realises that I feel a bit awkward about being watched, she writes messages on her mobile phone. Only when I put everything on the side and wait for the wasabi heat to dissipate does she put her phone away.

Only 13% of the workers in the fishing industry are female. From the 97 women enlisted in the female members of fisheries entry, only 12 are actually fishing.

Rimi is one of the 12 actual fisherwomen in Japan. Her father was a fisherman, but no one ever took women out at sea. “The kami for the sea is female, hence it is not good for women to work with the sea. It brings confusion.” is what she was always told. Sometimes she was allowed as a child to join the menfolk out, but only a few times. Rimi’s village like most coastal villages in Japan now; there is no longer enough work for her to stay, and so she moved to Tokyo where she worked in the newspapers trade. But she missed the life at the coast and returned to begin working in a fishing plant. Through acquaintances, she met Gate Co.Ltd., which ran some 20 Izakaya restaurants in Tokyo and had established links with local fishing folks in Kumano. She told them that she had always dreamed of fishing herself and the company said: “Why don’t you try it? Maybe we can find a way to support you.” Meanwhile, most fishermen had grown old and younger ones did not follow, so the people in Nigishima became supportive of her. She started net fishing. Gate Co.Ltd. does the brokering of her catches while she runs the actual work. She now has a team of three more fishing ladies who help her to process the catch. Being new to the business, she has new ideas, too. In Japan, there are now more than 20 million dogs and cats, but only 17 million children under 16 years of age. Pet owners want their animals to eat pesticide-free foods. Rimi had the idea to turn her bycatch into pet food which can be eaten by humans as well. In 2022, she won the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Food Award for this idea. “There is only decline or victory,” she says.

The situation in her home town is dire. The local school has shut down. There are not enough children to fill the classrooms, and people continue to move away. “Maybe if we get women to find work here, they will stay with their children.”

The work with the nets is hard and Rimi often needs men to support. But she also dreams of learning other fishing methods one day. “It will happen. One after the other.”

I ask her what she hopes for. “What I hope for.” She carefully moves the words around in her mind. “I would like this village to become a theme park for people to just enjoy nature. Not with machines and automatons, just quiet. Go fishing, sit on the quay. Live the slow life.” She does not dream of ever becoming rich. Being a fisherwoman and being able to support herself is enough for her. Maybe provide work for three more women and sometimes her 17 year old nephew, her sister’s son. “What I find so amazing about fishing is that with all other sorts of jobs, you need to set up a system. With fishing it is like this: the sea is abundant. Even if nothing else is around, there will be something in the sea to live off from. I want to continue this craft, this tradition of fishing for future generations. To enable people of the future to live off the sea.”

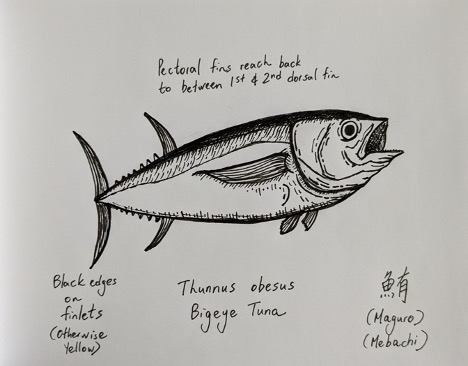

A bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus). Can be distinguished from a yellowfin tuna (T. albacares) by its larger eyes, longer pectoral fins, and smaller second dorsal/anal fin. Encountered at Choshi Fish market auctions in Chiba Prefecture.

Sketch by Isaac Yuen

Then she winks. “I want to show you something.” We get into her pickup truck and drive 300 metres to the tsunami wall that separates harbour and village, stopping in front of an old house. “Please come in.” It is a traditional space with tatami mats, a very basic living quarter. In the backroom behind the sliding doors are two university students crouched over a pile of cables. They are from the nearby Ise University for electronics and are about to install an underwater camera that floats above the fishing nets of Rimi`s fishing space. They come on weekends all summer long to work on their projects, living for free at this house supported by Gate Co.Ltd. “You know, when people of the fishing business leave, the monitoring of the sea also suffers. Until now, there were always enough people to report back on the state of the sea. But this has become less and less and I am worried who will watch out for changes.” The two students show me the footage they took in the summer. Clear and precise photos of the fish in the net.

“Would you like more young people to join?” I ask. “Of course! They can stay here. We need the exchange.” “But no one would be speaking Japanese,” I say. “With internet translation services, this is no problem.” Rimi says.

“Are you a fisherwoman now?” I ask Rimi. She smiles. “I am,” she says. I sense she is proud of this achievement.