Kushiro is on the southern coast of Hokkaido. After Japan ended its self-isolation period of more than 250 years in 1868, Kushiro became the port for trading with English and American ships.

In the last months of WW2, Kushiro was bombed and almost completely destroyed. In the following years, the population survived by organising the washo market, where they traded the few goods they had. With Kushiro being a fishing harbour, fresh fish was naturally sold in small stands. Researching old newspapers, whale meat was traditionally associated as something nourishing in Hokkaido during the winter months. It helped people survive after the war. In the city of Hakodate, whale soup is part of the New Year’s celebration. Each family has their own distinct recipe.

Today Washo market is a tourist attraction; we are told to get a bowl of rice with fresh sashimi for breakfast there.

A vendor approaches us, proudly pointing to his selection of whale meat, freshly caught on the previous day just off the coast. Dark red meat like steak, and marbled, fatty meat, from the tail. Another vendor hurries by and showcases hunks of whale meat, shaped and coloured like bluefin tuna. “Try whalemeat”, they hustle, “we give you discount”.

Japanese friends I ask about whaling in Japan will say they do not eat whale meat, but they also do not like foreigners to dictate to them what to eat or not.

At Kushiro market the vendors are literally pushing the whale meat at us. Their sales tactics seem proven by the flocks of tourists that arrive on giant cruise ships that dock the city. What to do in Kushiro? One customer at Tripadvisor: “This market opens at 8 am.

There are lots of stalls selling all types of seafood including fish, octopus, scallops and of course Hokkaido Crab. There is even a store selling whale meat.”

Maybe eating whale meat still carries an atmosphere of something that feels “forbidden”.

Whaling in Japan has been commercially banned for 30 years and since 2019 a quota has been established, allowing commercial fishing or “harvesting” of whales again – as the main player Kyodo Senpaku phrases it. They are a consolidation of the whaling departments of the Japanese fisheries and highly subsidised (5.1 billion yen (US$47.31 million) for commercial whaling in 2019).

According to their communication papers, Japan hunts 25 sei whales, 187 Bryde’s whales, and 167 minke whales every year.

Part of one of the Minke whales now lies cut up in front of me on a polystyrene tray.

Like my friends, most Japanese people will not eat whale meat. 89% of the population has not bought whale meat, sold in fewer and fewer supermarkets. It has a stigma of something that feels shameful or simply out of fashion.

That is something Kyodo Senpaku wants to change.

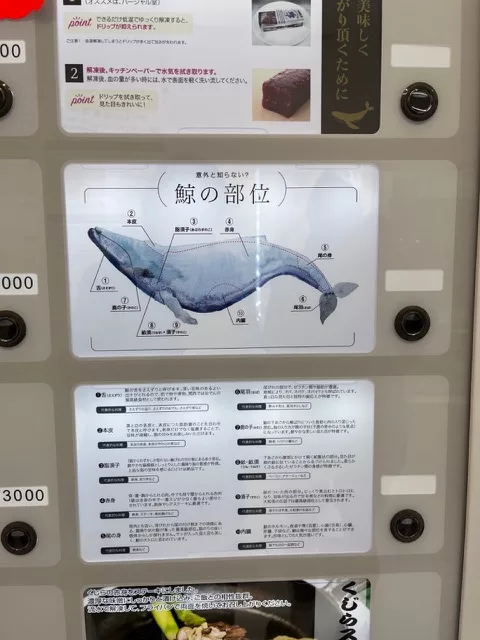

In January of this year, they opened a vending machine in Yokohama near Tokyo. It is located at Motomachi, an upmarket shopping district, next to a health food shop called The Cashew Tree and not far from a shop that sells German cuckoo clocks. It is a tiny cube-like building, white, with the Kanji for whale, or kujira, over the door. It has a designed, clean look. “Protect by eating. The future of the sea.” reads a poster inside the shop.

One vending machine specialises on cosmetic products made from baleen. “It will make your skin glow. Powdered whale will lend strength when being tired. Treat your skin with the richness from the sea.”

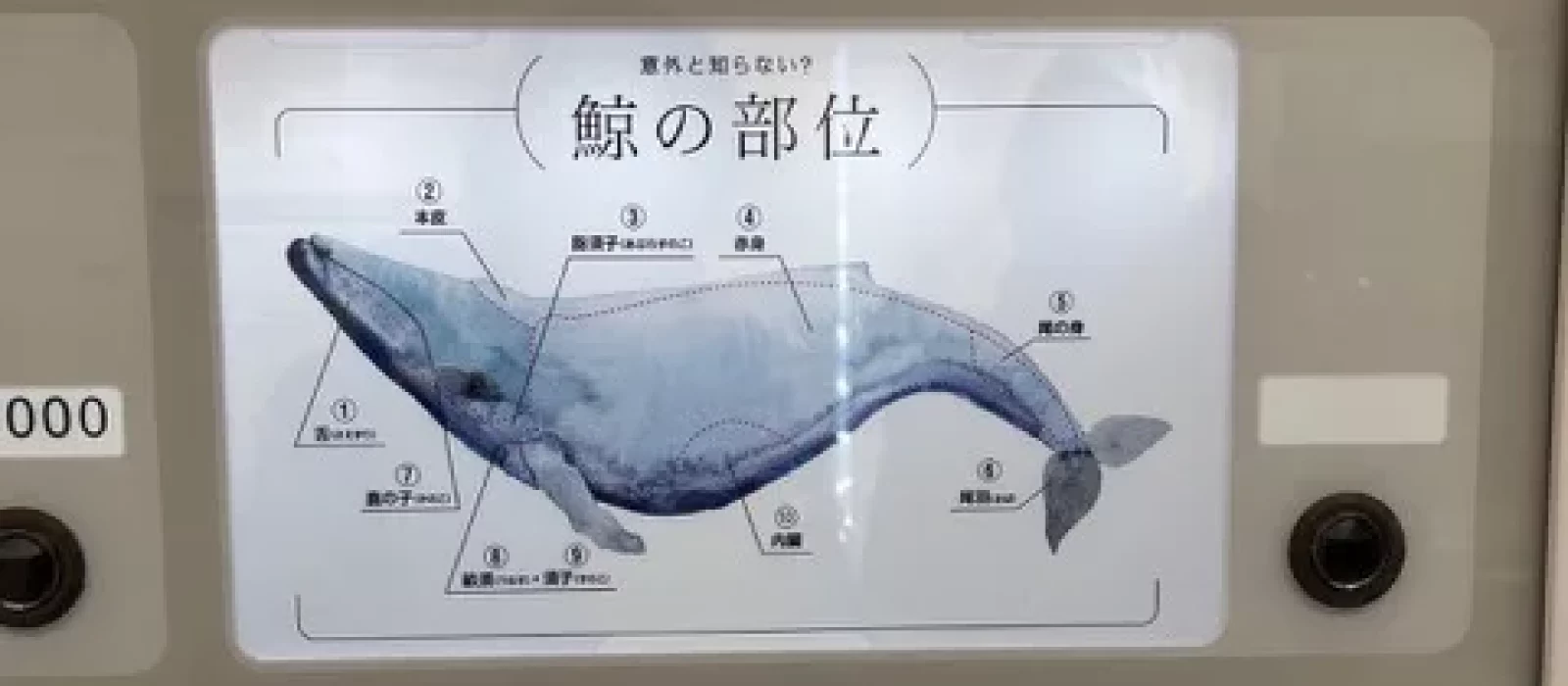

Three other vending machines sell whale meat, “nostalgic” whale bacon, sashimi, steak. There is info material on how to prepare the meat and what to season it with, as well as some guidance on which part of the body the meat is taken from.

Several posters present written information from the Kyodo Senpaku. Here is a translated excerpt:

“Too many whales are one of the causes of disrupting the oceans ecological balance. Whales consume 3 – 6 times more biological resources than humans in the world’s oceans. The depletion of marine resources has become a problem. One of the solutions is whaling. By catching these whales, we protect approximately 60,000 tons of marine resources each year. In other words, whaling can help protect the richness of the ocean.”

Thankfully, people are doing their own research: In Hokkaido, more tourists now go whale watching than look for whale meat. 33,451 whale watchers were counted in 2019 and this business is expanding, providing a livelihood for ex-whale hunters.

We spend 20 minutes in the shop observing people coming in and walking by. Two men, one younger and one older, seem to bond visiting the shop. “Yikes, bacon. That really is a bit weird.” they say to each other. “And this looks a bit strange.” In the end, they leave with one packet of whale steak.

Other people come, not buying anything. The shop is a novelty. Kyodo Senpaku wants to open another 100 shops in the next 5 years all over Japan. Another PR action is to give out free whale meat to schools. They might be underestimating Japanese mothers who are very well aware of the health risks associated with the heavy metals in whale meat.

A small window in the back of the shop serves as a mailbox. Customers can drop a handwritten note in with feedback. I pick up one of the empty papers and a pen, then put them back again unused.

Side note:

That very morning in Choshi we visited the gravestones for whales at the local shrine for fishermen. Besides whales there were also gravestones for tortoises. (see photo)