Kombu is the name for giant kelp in Japan and it is used for cooking dashi stock, the kind of soup that accompanies everything in Japan. While it can also be made from shiitake mushrooms or katsuo, a kind of tuna, the kombu dashi is thought of as light in taste, elegant, healthy and nourishing. And it is considered a potent ingredient in Chinese medicine.

I encountered Kombu already on Haida Gwaii, where it became an interesting focus point for the discussions on the borders that define the territory of the Haida Nation. The Nation claims that their stewarded land extends far into the sea, not last because of the kelp forest underneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean. Talking to biologists I came to not only see them as a mirror image of the forests on land, but also of a place that contributes to the diversity of life on land. The kelp forests offer shelter and protection especially to the nurseries for various sea creatures. Yet, with climate change and the near extinction of sea otters (who eat sea urchins), they are under threat and sea urchin barrens spread out where once lush kelp forests swayed with the currents. But that is another story, that I tell here: https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/haida-nation-in-kanada-im-einklang-bis-die-europaeer-kamen-dlf-kultur-6472a574-100.html

In Japan the eatable kelp only grows offshore Hokkaido and has been harvested since the 7th century. So I was surprised to see the main kelp industry in Ikuji, a small town near Toyama, roughly 1500 km south of Hokkaido. The story how that came to be is an interesting one and I learned it from Mr. Aimono, the director of the Aimono Kombu manufactory.

The soil in Ikuji is not very good for agriculture. It is porous and serves the many wells that spring up here, but try to farm anything and it becomes hard. The fishermen are good in catching enough fish to live off, but with the entire bay having decent fishing grounds, it is hard to sell the local fish for a profit. Driven by survival, during the Edo period, some fishermen sailed in the summer to Hokkaido and specialised in Kombu harvesting. The best Kombu can be found along the Shiretoko peninsula. One rows the boat offshore, sticks a giant rod into the water and starts twisting it. It will eventually get a grip on a kelp and can be pulled up. One needs strong arms, but otherwise no special skills. (Some days later I visit the Kombu beach at Shiretoko and talk to a fisherman who is working with the kelp. He claims that nowadays more skill is needed, as the expectations on Kombu are so high, especially at this location, which is known for its highest grade of Kombu: “The Kombu picker needs to have a good eye see through the surface of the water and to judge from above the quality of the Kombu”). The Kombu would then be processed during the two months season in July and August, right there at the beach. Then it was sent down on so called Kitamaefune (translates roughly to “Boats that have been to the North before”). These boats would unload the Kombu in Ikuji and then sail further south, at each port loading and unloading goods from other regions, making a fortune on the way.

We have to put on the pink factory suits to enter the manufactory. Pink, because all the employees working with the Kombu manufacturing site are ladies. Women work at the beach to dry the Kombu. It is women who will prepare it for its journey south. At the shops and storage houses women keep track of quality and logistics. Even when we visit, it is women who will brew the coffee and the Kombu tea. But these are the behind the scenes stories.

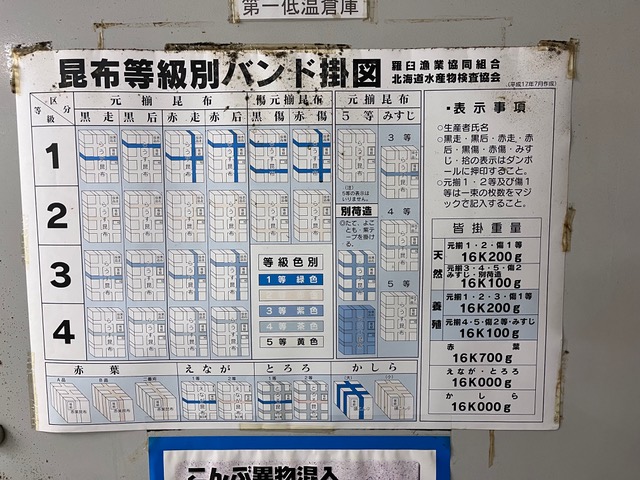

Mr. Aimono takes us upstairs to the storage rooms. The scent of umami is overwhelming. When I try to recollect, I think of the essence of the sea. The Kombu is packed into boxes and the binding pattern of the string around the boxes provides the key to the quality inside the box. The thought after Rausu Kombu sells for 218 dollars per Kilo.

Lately Noma restaurant creative chef Mette Søberg visited Mr. Aimono’s manufactory. Aimono Kombu was chosen to be the main ingredient in Noma’s new line of broths that will marketed to foodies and health conscious worldwide.

Today, in Rausu, at the Kombu beach, far up North in Hokkaido, other stories drift in. The close encounter with Russian islands in sight causes a lot of friction on the daily basis with the fishermen. When they cross the invisible border, they get handcuffed and sent to prison.

And south in Toyama, miles away, another narrative unravels. Driving by we find a Lawson Convenient store that offers Halal products. Why here? Soon we see the street lined with used car dealers, their signs in Russian and Japanese. Other empty lots on the side of the road offer container housings. We do some research. Until August 2023 Toyama was the biggest exporter for Japanese used cars to Russia. Especially since the start of the Ukrainian war this business thrived and as a result used cars have become expensive all over Japan. To ship the cars, Pakistani immigrants were invited to Toyama. 480 of them reside in Izumi, a part of town, that has been coined Izumi-stan. I read about Koran being left burnt on the hoods of cars. But also of local shops offering halal foods. And the best curry places this part of the world, run by Pakistani chefs.

The sea is an open space. Not only goods are traded, but people and cultures. For some it is a one-way journey.

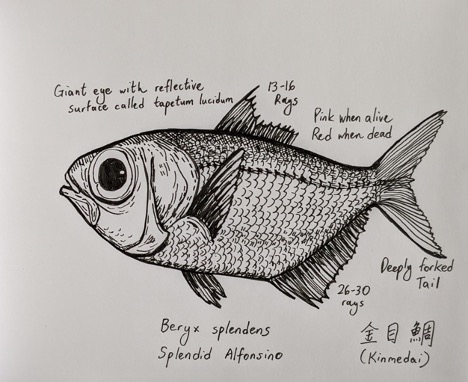

A splendid alfonsino (Beryx splendens). Also known as kinmedai, or golden-eyed snapper. An increasingly prized fish that lives at depths between 200-800m. Encountered at Kurobe Fisheries Cooperative Market, Ikuji Town.

Sketch by Isaac Yuen

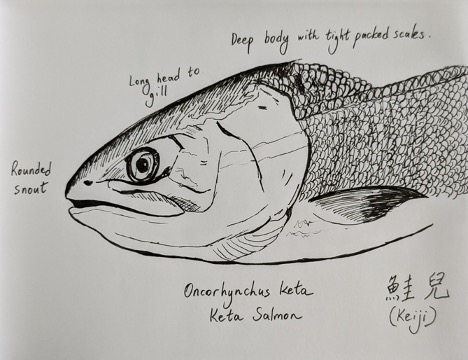

A keta or chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta). A non-spawning juvenile caught at sea is called a keiji, and is highly valued for their fat content (20-30%) and rarity (1 in 10,000 fish). Encountered in the pages of Shiretoko Rausu: A Handbook on Marine Life, from Rausu in eastern Hokkaido.

Sketch by Isaac Yuen