Six of the ten woodblock prints by Hokusai’s Chie no Umi series are situated by a river. Net-fishing, torchlight fishing, basket fishing, fly fishing, rope fishing and waiting nets all portray men engaged in tapping into the abundance of the rivers.

I found it hard to follow him there.

Finding his rivers or fixing the exact locations from where he painted them became a piece of detective work. Looking at old maps. Consulting with art historians. Researching in Japanese encyclopaedias. Some of his old rivers no longer exist, while others have been altered by dams and channelisation. When standing at their shores now, nothing evokes the blue waves and the tranquil backdrops of the original Hokusai prints.

A handout by the Japanese River Association notes that Japan’s rivers are rather short compared to rivers in other places of the world, flowing directly from the mountain to the sea. The Association includes a map on which they mark areas that have more than five severe floodings during a ten year period. Half of the map is painted in red. Typhoons and seismic movements regularly intensify the danger of flooding and landslides.

“Japanese rivers are like waterfalls,” said the Dutch engineer Johannes de Rijke, hired during the Meiji period to help alter the Japanese landscape, where most of the population and property are on vulnerable alluvial plains. As a result, most rivers were tamed.

Many of the river shores we visited are flat, uninhabited land. We spent a day hiking along the Tone River. Crows and kites circled the air that buzzed of insects. We passed an incineration plant, some baseball fields, and saw the city of Kashiwa and a food production plant in the distance. Along the river was a bicycle path used by a handful of joggers and bikers. The immediate shore was overgrown with no access point to the river itself.

Other rivers I have written about in this travelogue don’t feature such a green belt anymore. Rivers in Tokyo run between and under the high rise buildings and highways. Others have become a container for fluid industrial waste. “Where I grew up, no-one would eat the river fish,” one government official told me during an interview.

We went searching for natural rivers in Japan, undamped, untampered. To hear and feel into the abundance of life, the biodiversity, that a river enables, the habitat it provides. Only one such river exists: the Shimanto River at the far south of Shikoku Island.

It takes two days to drive to the Shimanto once we landed on Shikoku by ferry from Wakayama. A mountain range divides north and south of the island. The Shimanto region is remote in every sense: Ando Tadao, the Japanese architect, said it was easier for him to overlook a building site in Paris than on Shikoku. The travel time to reach Paris from Tokyo is so much shorter.

One attraction that was featured on roadsides in Shimanto town is an eco-park with dragonflies. 90 species can be found here, more than in any other place in Japan. Once they were everywhere in the satoyama landscape, whirring over rice paddies and irrigation ponds, serving as pest control and signs for a healthy biosphere. At the Tombo-Park in Shimanto, blue-eyed or yellow winged species fill the in-between spaces.

An entry in my diary:

“To be at Shimanto is to enter the river. It is an old kind of river, a connection to this body of water emerges right away. The woman at the Tourist office in Shimanto city when I asked her where is the river the most beautiful had answered: Uchi no kawa ha fushigi na kawa nan desu. Doko ni ittemo kirei desu. The river here is mysterious. Wherever you go it will be beautiful.”

The other attraction are the Chinkabashi bridges crossing the Shimanto River, so-called sinking or submersible bridges. They were built by simple farmhands with the materials available. To make them last longer, no railings had been attached, so when the river flooded, water could pass through the bridge, leaving it unharmed. Later they were made of cement, simple crossings, that invite to sit on or under. They have become an odd landmark, a relic of a time when one had to do with what one had, to not only make everyday life possible, but to survive with what was available.

Hokusai’s Chie no Umi series was never completed, and we are left to speculate what other sights near bodies of water the artist might have shared with us if he had continued. Japan then was a closed nation, where travel to the world beyond the islands was strictly forbidden by the Bakufu, the military government.

As a result, everyone’s interest turned inwards. Instead of becoming a stifled country, arts, philosophy, and fashion were all infused with a creative spark that came from having to do with what is there and by exploring that to its full extent.

We are only slowly beginning to understand the dynamics of Edo Japan, which remained a closed country for more than 250 years. What evolved was a nation that was almost exclusively self-reliant — culturally and economically. Recently, academic papers are emerging to explore the socio-economic impact of this closed period from an ecological viewpoint: When all materials had to be generated from sources within, the management of natural resources became extremely important. As a result, an early version of what we now call the circular economy was widely practiced. Goods and tools were designed to be easily repaired or even be modelled into new tools after their lifecycle was over. The profession of the paper umbrella repair shop appeared. Getas, clacking sandals that must have formed that background beat of Edo period soundscape, are even today thought to be one of the most perfectly designed everyday products: their usability, endurance and repairability cannot be compared with anything we produce today. Kimonos could easily be sewn into new textiles, while fixing or repairing broken goods turned into an aesthetic ideal, as with Kintsugi method with broken pottery or the Kogin Sashiko stitchings of Northern Japan.

It is under this premise that the Chinkabashi bridges become even more memorable. They represent architecture that adapts rather than forces itself onto a landscape. Durable, resilient, easy to repair, over the years they accumulate their own charm, collecting stories of peoples’ crossings and passings over the narrow stretch of asphalt. Each encounter with another on the bridge feels like a lesson in humility.

The Shimanto is a mysterious river. It is beautiful, from whatever bridge one looks upon it.

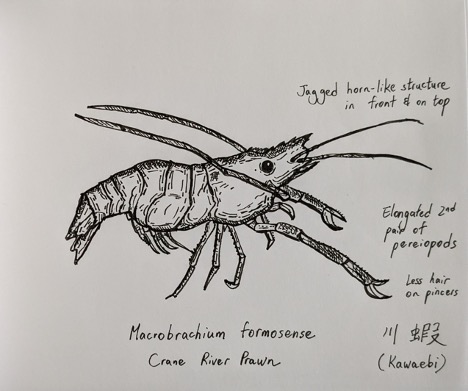

A crane river prawn (Macrobrachium formosense). A freshwater species that inhabits the Shimanto river along with two others in the same genus (M. japonicum and M. nipponense). Key feature is the elongated second set of forelimbs that end in pincers. Encountered at an izakaya restaurant in Shimanto-shi, Kōchi Prefecture, where they are commonly served as bar snacks.

Sketch by Isaac Yuen