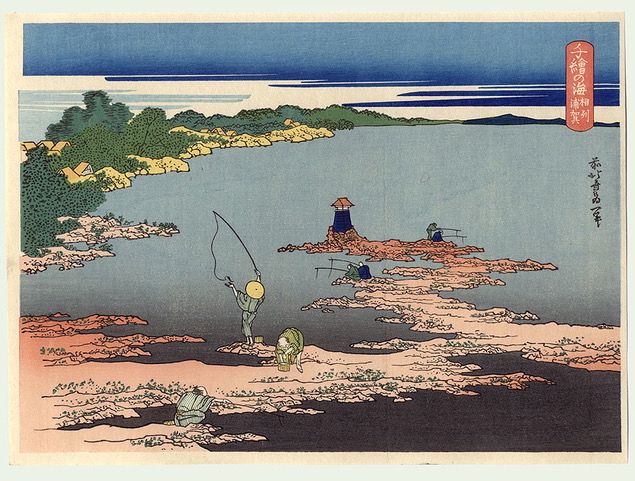

The Hokusai print “Uraga in Sagami” is my favourite from the Chie no umi series. Like all the pictures from this cycle, it depicts men engaged in fishing activities within a Japanese landscape. Here, at Uraga, the land curves towards the horizon, while the promontory, where the fishermen stand, leans towards the land. The body of water kept in between this space lends its shape to a pewter-coloured crescent moon. These swayings and trajectories are enhanced by a fisherman, arching his body backwards, checking the bait on his rod. He seems to be creating another half-moon body, this time a slightly fuller one appearing in the space between rod and string, while in the center, holding land and sea, stands a solitary stone lantern. Powerful, assertive, a solid reflection by Hokusai on how we as humans have learned to manage and navigate the ever-changing sea. While ebbs and floods alter land and sea to the moon’s cycle, this human-built monument remains steadfast, still

I also sense an escapist mood in this scene of fishermen, out on an evening at the bay, their rods hanging low over the water. It connects me on a low frequency with their daily routines and grants me a glimpse into the geopsychology of Edo Japan more than 250 years ago. What tasks did they spend their days with? What thoughts drifted through their subconscious, let loose by the act of sitting still?

The scene reminds me of the men near my home by the Oder river, who during the pandemic would spend hours at the shore fishing. As I passed them without speaking and only nodded as greeting, I could only assume that the act of fishing gave them agenda during that time out of time. While society was locked in, fishing allowed them to escape, gave them space to breathe, to be by themselves, engaging in an activity that might or might not be rewarded with a catch. At Uraga, while time passes from daylight to nightshade, the prospect of returning home with a fish fades away. Fishing becomes an exercise of something else: of being out, near the water, feeling into the waves, the mood and the body.

During the beginning of the 19th century, when this picture was etched, Uraga was still abundant with fish. It was probably enough to hold the rod over the water for a while before a fish would bite.

When we arrive at this exact same spot, almost 200 years after Hokusai sketched this scene, the bay is still filled with water, but its shores have changed dramatically. In the distance, the city rises. Tokyo’s waterfront is made up of industrial chimneys and high rise buildings; their glass fronts glitter like a silver seam, sealing off the bay to the North. The city pulses invisible chemicals and run-offs into the bay, turning its water into one of the most polluted of the nation. Tanker ships, bigger than factories, move this way and that across from our field of vision. Filled with goods, feeding, fuelling the needs of the rapacious city.

The light of the day is just beginning to dim. People come here for an evening stroll from the nearby village. Lovers, an old couple, dog owners. A solitary man sits by the side, his eyes focused on the steel coloured water. Someone has left two plastic toy figures sitting on a rock looking out at the sea, avatars of others having cherished this moment. The parking lot right behind the bay is clocked with a strict time measurement. At 8pm the rates will be cheaper. A small van is already parked here, with a man sleeping on his seat behind the wheel, drifting in and out of dreams.

Earlier that day, we visited another bay, half an hour drive south from here. This was where the Japanese sound artist Toshiya Tsunoda recorded his track Maguchi Bay, released in 2007. Tsunoda held his microphone out to listen to its soundscape and realised he was capturing a low frequency underneath the normal environmental sounds. Unnerved, he started thinking where this low vibration stemmed from. It was neither wind nor distant ship. A fisherman later gave him the answer: “It was the vibration of the underwater currents hitting the pier supports where they met the seabed. The low frequency that I observed is an essential feature of Maguchi Bay and it’s directly related to the structure of that place. It only became a fishing bay when a lot of breakwaters were built to calm down the terrible sea currents. So there is a local history that I became aware of through the low frequency. I came to love the place.”

Toshiya Tsunoda would later describe these recordings as a way of seeing a landscape with his ears: “If you think about it carefully, the activity of an actual space always moves. If you put a contact mic on the ground or the wall of a space as I do, you can hear the standing wave that persists in the place. There is a complex mechanism there even if the wave seems simple. Probably all things – material, construction, temperature, humidity and so on – that concern the place might be a factor here. Place is always moving, like a sleeping cat.”

The stone lantern in Uraga still stands, though it is bigger now than then. A sign reads that it was built in 1690, a symbol of the Tokugawa Bakufu government. Some decades after Hokusai had captured this “tomei”, this light guided a strange and foreign ship into the bay, it would pass by the lantern and anchor at Uraga. The ship was black and made of steel. Its commander was Commander Perry, who came to open up Japan to the West. The light of western enlightenment streamed into Japan from this very moment while the old ways slowly but gradually sank back.

On this evening, the sun sets behind us and casts her light onto the stone lantern, setting its sandy grains aglow from outside. We try to find the exact spot that Hokusai used as the vantage point for his painting. It must have been towards the South of the shore, where now a villa built in a neo-Baroque style invites only the privileged. The pool inside is empty and there is no sign at the door. Suddenly the water in the sea starts moving. Mullet fish jump out from beneath in perfect arches. What happens beneath the waves we do not know. The Shimanto is a mysterious river.