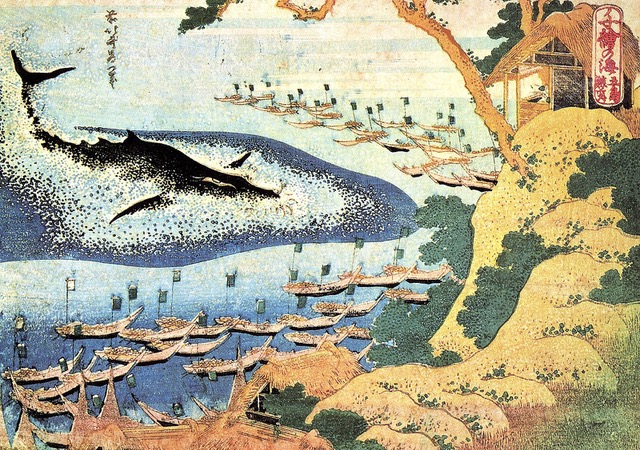

One of the Umi no Chie prints by Hokusai was labelled ‘whaling at Goto Island.’ He places the viewer on a lookout to watch from above the last moments of a whale hunt. 42 small wooden boats surround a whale of gigantic size. Sea spray gushes around the animal, its enormous eyes bulging. The whale has not yet given up and the boats keep harrying it from at a safe distance. Looking through photographs and maps, I find the lookout that this picture is drawn from: Nakadori Island, one of the five main Goto Islands.

Monday morning: I take a high speed boat to Nakadori from Nagasaki. Aboard, an idol band is blasting songs on the TV screen that no-one watches. It is a rough ride of 90 minutes to Arikawa on the northern tip of the island. So-called etiquette bags are being handed out in case the sea gets too rough, but most of the people on the boat are locals and are steadfast.

Upon arrival, the statue of a grey whale greets me in the port along with a smaller one of a dolphin. The public toilets show gaudy whales dressed as men and women. Even the curtains of the local soba shop sports a whale pattern, while the island mascots are cute figures with whale hats adorning chubby faces. Just outside the arrival terminal, made of heavy grey steel, is a modern whaling harpoon canon, used in Japan since the early 20th century. The bolt, the hooks: I can almost hear the thump it must have made when it penetrated the body of a whale. First the muffled blow, then the deadly explosion within the whale’s body.

I soon find the shrine I was looking for. Kaido Jinja is entered through a gate made of gleaming whitebones of whale jaws. They have been painted, but the texture is still visible beneath the colour. I pass under as if it was a torii, a classical Shinto gate, and the path climbs up steeply through a subtropical forest. Bird calls reach me from the surrounding treetops with no bird in sight. The deeper I enter this hill, the less I can hear them. By the time I reach the top, there is only silence.

I stand in front of the Hokura, a small enshrinement of the local deity. The stone slabs in front of its three altars are swept clean. Someone is taking good care of this place.

Between the years 1617 to 1619, more people than usual had drowned in Arikawa bay. It so happened that this occurred always on the same date, of July 17th. When the dragon god of the sea appeared in a dream to one of the local fishermen, he built this shrine and danced in front of it. The drownings became less frequent. Since then people come here to pray for a safe return from their whaling trips.

A cat watches me from afar and I follow her. The path I had come up crosses over the top of the hill and descends again through a bushy back entrance. Down below is the town’s fishing harbour. I get a glimpse of the ferry building; its structure mimics the body of a whale, with the baleen protruding as the roof.

At the harbour, eight young fishermen clean and fold their net. It covers the entire ground and they work at it for a long time. When I pass by, they wave at me and do not mind me taking photos. At a far corner of this same net, an older man sits hunched over, fixing places in the net that have ripped. He has come on a Vespa, and his sawing tools are stored in boxes, placed at an arm’s length away. He invites me to sit down with him. “It’s bad weather. This is a good time to fix a net.” We talk for a bit, but his dialect is hard to understand. He tells me that he has been to Spain and that he once swam with a whale. He wants to give me one of the bamboo needles is uses for fixing the net but I don’t want to take this thing he has carved himself away from him. With a thick felt pen his name marks each needle: Yoshiro. He urges me to have a look at the whaling lookout. I should be able to look upon the entire bay, he says, and so I move on. “And anyways, there aren’t many fish left to catch.” This is something I have been hearing a lot on they journey.

I leave the harbour through a narrow passage towards the hills. To the right, some stones are placed next to each other, like simple stupas. Each of them is adorned with a sake cup or a beer bottle. The cigarette stumps on the ground indicate that people stand here for longer, taking a break. There are also some wrappers for painkillers tossed on the ground. Fishing is still one of the deadliest professions.

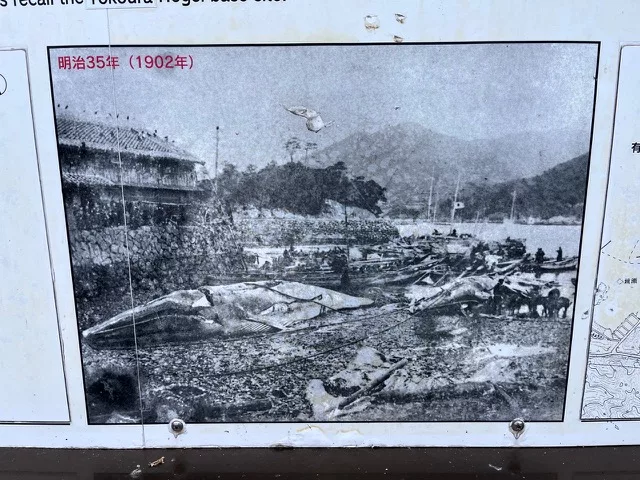

I arrive at another bay where once whales were dragged on land and taken apart. Later, I will learn at the local museum that all the men in the community would help with the task. The night before the whaling season started, the men would gather at the local shrine, drink sake and eat ceremonial foods, singing songs together and dancing a certain folk-dance. That helped to synchronise everyone into the same rhythm. In the old sketches at the museum, children came with their mothers and peered through temple windows to watch their fathers preparing for the hunt. Later, at the end of the season, a special ceremony was held in which the names of the fisherman that did not make it back alive was read aloud.

Where the whale carcass was once cleansed, I now see some young people diving. It is a cloudy day and they are shaking from the cold. When I ask then what they are up to they tell me this are from Nagasaki University, diving for plastics. Because of the currents from mainland China, the bottom of this bay is covered in more plastic than is the norm. They are researching the effects of the plastic debris on seagrass growth. I think of the concept of plastic as a hyperobject, as as theorised bz philosopher Timothy Morton. How we cannot fathom the world without plastic anymore. I ask for permission to interview a young woman from Kerala, India, who studies marine biologyat Nagasaki with this group. How she got interested in this research topic, what they have learned so far. Afterwards, I continue my walk and finally reach the old whaling lookout that Hokusai depicted. It is on top of a local hill and from here I can see far out into the horizon. Presently it is maintained by the local Rotary Club, but once someone had to sit here all day and watch the sea. If a whale was seen, the scout would call out to the village and the villagers would row out in their tiny, fast boats. They would stretch out a net across the bay and begin beating a drum made out of whale skin. The whale would dislike this sound and try to swim away and so get stuck in the net. Then the harpoons would set in.

There is another whale shrine on this hill,dedicated to the wellbeing of the whales. Their prosperity, this shrine suggests, meant the prospering of the villagers. It was erected by the Clan chief from mainland Japan. The profit from the whaling went straight into his pocket, while the villagers themselves earned little . Because of this, one custom from the old days was common: Kandara, or the habit of stealing whale meat while the whale was being cleaned. The act of stealing the meat for one’s own purposes was accepted by everyone.

Before I get back on the ferry, I see the upcoming Halloween decorations outside the ferry terminal: Cheerful looking whales and dolphins wrapped in plastic bags hanging from the trees.

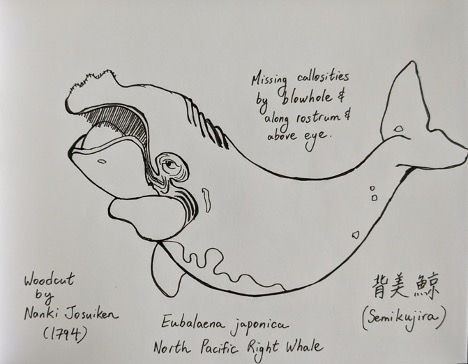

A North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica). Replica of a woodcut print by Nanki Josuiken from 1794. Commonly depicted in Japanese historical art on whales, the species is currently critically endangered, with the West Pacific population numbering in the low hundreds. Encountered in a display at the Toba Sea-Folk Museum in Mie Prefecture.

Sketch by Isaac Yuen